|

The principles and applications of rehabilitation are similar across both equine and human patients, and there is much we can take from the human literature to help us design our equine rehabilitation programs. Goal Setting As a practitioner we must consider not only what are we trying to achieve in our programming, but what are the goals of the owner. Points to consider include:

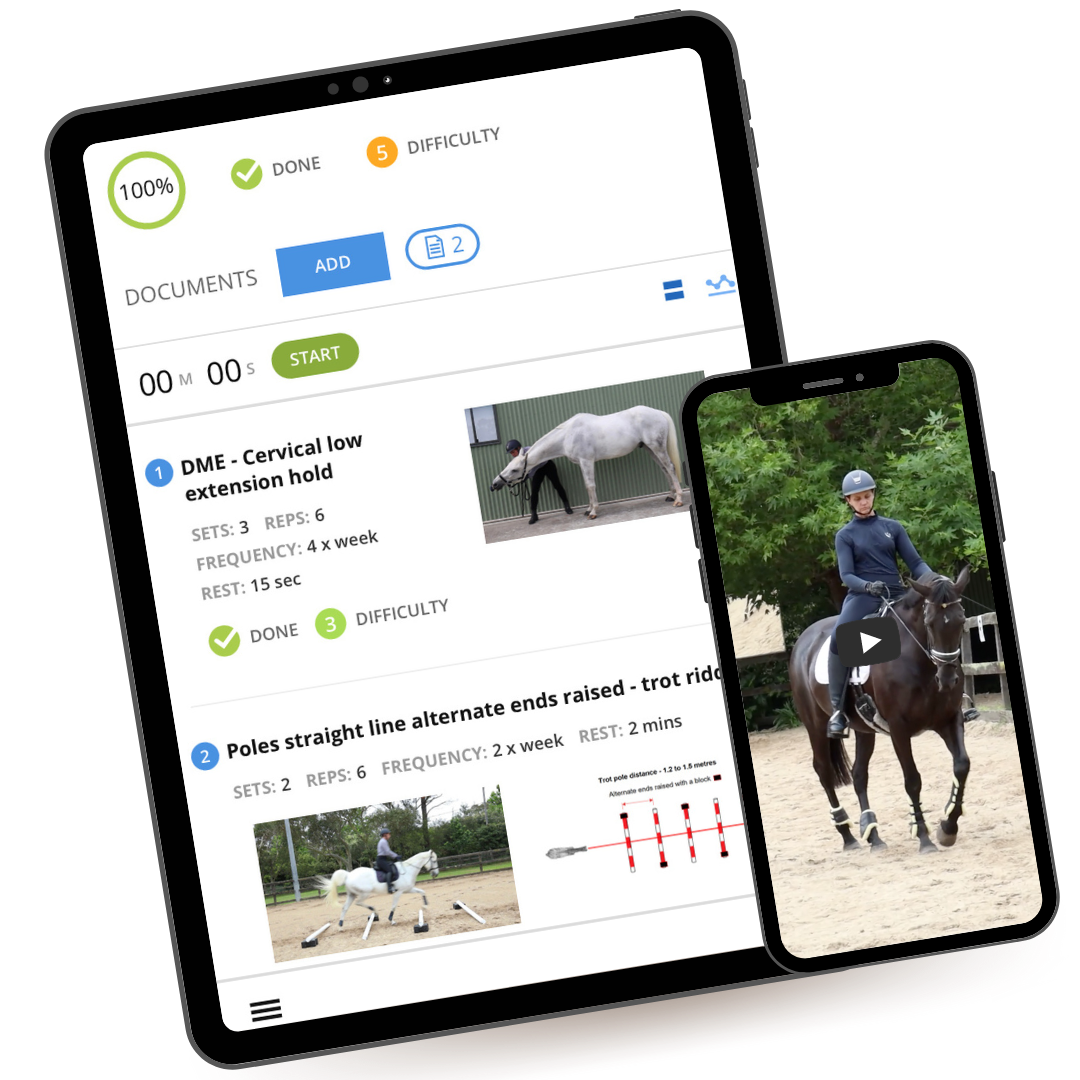

Program Design Before we start to plan our programs, it’s important to consider the capacity of the owner. We want to ensure that we set our owners up for success and we need to consider the owner’s ability to commit to our rehab programs. Once we start to plan the program, some of the areas to consider include: Strengthening Strengthening exercises are used to progressively improve neuromuscular control and load and strengthen musculoskeletal tissues, with the overall aim of strengthening to adapt the horse to the demands of performance. A basic principle of training is that a single exercise session leads to fatigue and mild cellular damage which, in turn, results in short-term adaptive responses. When exercise is performed regularly and training stimulus is increased gradually, the adaptation that occurs during the recovery period of a single training session leads to an overall improvement in performance. Thus, the basis of any training program is to continually provide increased levels of stress to the physiological systems to improve performance. However, it is important to appreciate that there is an upper limit for these adaptations and that individual horses will differ in relation to how well they can cope with this stress. When training is too vigorous and/or rest periods between training sessions too short, performance is reduced due to an imbalance between training stress and recovery. The time before exposure to the next training stimuli should be of sufficient duration to allow time for the training effect (adaptation) from the previous session to occur. If not, then performance decrements can occur in the form of earlier onset of fatigue within each session. Recovery time / strategies are equally as important to schedule in a program as load! Mobility Stretching is one of the most controversially debated techniques with constantly changing views on its positive and negative effects on muscle strength and power. At present, most of the literature in relation to stretching has been conducted in humans, with very little in horses. Therefore, we currently must apply much of what we know from the human literature and in other animal models to our equine athletes. There is a general belief that static stretching promotes flexibility and improved athletic performance. However, in more recent years researchers started presenting the potential harmful effects of static stretching on strength- and power-related activities and static stretching started to fall out of favour in human sports as a result. However, findings from two recent comprehensive systematic reviews demonstrated that short-duration acute static stretching (≤60 s) had minimal to no negative effects on measures of strength and power as opposed to prolonged stretching (>60 s). The specific causes for this type of stretch induced loss of muscle power is not clear; some suggest neural factors while others suggest mechanical factors. In studies in both horses and humans, stretching has been found to have a positive effect on increasing joint range of motion. Several studies have suggested that the increased flexibility generally seen after stretching regularly over a period of time is related to an increased stretch tolerance, rather than increased muscle length, as is commonly thought. This is likely due to a reduction in the perception of discomfort associated with the stretch, allowing the person or horse to be more comfortable going into a greater ROM. More research needs to be done to fully understand this process. There is no real consensus in the horse or human world on how best to prescribe and dose mobility programs. Although there is a massive number of studies in this field, it remains unknown as to what are the most effective stretching parameters to be performed to induce viscoelastic adaptations within the muscle tissue. Cardiovascular Training The aim of cardiovascular training is to increase heart rate without aggravating the injury. Some examples include swimming / water walker or treadmill, ridden submerged water training (RSWT), lunging / long lining and restricted riding. Preliminary results from a recent observational study have established for the first time that RSWT can be classed as a moderate submaximal intensity exercise in elite event horses whilst restricting an increase in temperature of the distal limb that is commonly associated with tendon rupture. It involves submerging a horse up to sternum height and trotting for set intervals. Training loads can be measured using tools such as heart rate monitors, GPS and activity trackers. Proprioceptive training The aim of proprioceptive training is to increase the speed and efficiency of neuromuscular control to prevent reinjury. Ligament, tendon, and joint injuries are often accompanied by proprioceptive impairments, which often persist after the acute injury phase. The closed loop feedback system implies that when a movement command is generated the intended motion is compared with feedback regarding the body’s status and the relationship with its environment. From a neuromotor control perspective it is an extremely valuable tool to utilise the closed loop to facilitate appropriate or change an existing trunk or limb motion in equine rehab and performance enhancement. It can be utilised very effectively in the horse by applying sensory facilitation aids directly to the horse’s skin or body, such as tape, resistance bands and tactile stimulation bracelets. You can also utilise progressive balance exercises such as weight shifting, stability pads, picking up opposite/diagonal limbs, poles and walking on different surfaces. Measuring progress Measuring progress is vital to help us to amend or progress the program. Ideally it should be objective where possible. Providing owners with simple tools to measure their own progress along the way can be extremely motivating and make them feel in control of their progress. Simple examples might include regular photos to monitor posture or muscle bulk or counting the number of times a horse trips or displays specific pain behaviours within a session. Progression of rehabilitation programs includes type of activity, duration, intensity, frequency, and complexity. Consider changing just one variable at a time in order to avoid overloading too quickly. Pain Management In conjunction to the exercise component of a rehabilitation program, other interventions such as medication, manual therapy and electrotherapy may play a role in helping to manage pain and encourage healing. It’s important to consider that exercise plays a role in pain management too and reassure our clients not to be fearful of encouraging movement and exercise in their injured horse. Exercise Compliance Compliance is one of the biggest challenges therapists face in regards to rehabilitation programs. There has been a recent increase in the use of apps to deliver home exercise programs, as opposed to more traditional paper handouts. Preliminary research suggests in some groups there may be increased compliance and improved outcomes in patients with the use of app-based delivery of programs, however communication with the therapist was a key part of the intervention. Further research is needed, however apps can be an effective way to motivate and check in on patients, along with being a time saving tool for the practitioner. EQ Active is an equine and rider specific platform, that also allows you to access canine and human content from our partners. To learn more and to try it free for 30 days, head over to www.eq-active.com References

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

kristin & EmmaWe've been practicing as human & equine physiotherapists for more years than we'd like to admit (it will show our age!) Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed